It is estimated that 1 000 women per day will experience perineal suturing following vaginal birth in the UK alone (Kettle et al, 2010). The aim of suturing perineal trauma is to achieve haemostasis, minimise bleeding, reduce the risk of infection, and assist healing through primary intention and correct anatomical alignment, maintaining overall integrity of the pelvic floor.

Midwives must be mindful that perineal suturing can be a traumatic experience for some women and can have an impact on their psychological wellbeing (Green et al, 1998). Therefore, it is vital that midwives are adequately trained and able to provide each woman with clear information regarding the procedure to be undertaken, so she is involved with her own care (Table 1).

|

|

After the information has been clearly relayed, and consent has been granted, ensure the woman has adequate analgesia before proceeding with the assessment and repair. It has been suggested that inadequate pain relief or proceeding with the repair before permitting analgesic methods to have taken effect is often experienced by women (Sanders et al, 2002).

Absorbable synthetic suture material has been associated with less perineal pain and wound breakdown than non-absorbable material (Kettle et al, 2010). Additionally, a continuous suturing technique is preferable to interrupted sutures because the former is associated with reduced short-term pain (Kettle et al, 2007). The technique of repair and type of suture used for repair all contribute to the levels of perineal pain that women may experience Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2004).

Bedding must be clean and dry to protect skin integrity, reduce the risk of skin abrasion, and prevent pressure sores. Ensuring the woman is as comfortable as possible, affording her privacy, maintaining her dignity, and guaranteeing that she is not left unnecessarily exposed is essential to maintaining her psychological wellbeing whilst she is undergoing this operative procedure.

Be sure to undertake a swab count with another health-care professional before proceeding, and then again once the procedure is complete. Moisten the tampon with obstetric cream, then insert it gently into the vaginal vault. Secure the tampon tape to the drape to reduce blood loss for clearer visualisation of the injury.

Imagine the perineal trauma in the shape of a diamond, then infiltrate the perineum, remembering to first draw back to avoid intravascular injection of local anaesthetic. Infiltrate either on the left or right lateral point, directing the needle up toward the top point of the vaginal wall. Slowly inject the local anaesthetic whilst withdrawing back to the initial insertion point. Keeping the needle in position, reverse its direction while inserting along the perineal aspect, toward the bottom of the diamond, utilising the same technique of injecting whilst withdrawing back to the site of insertion. Remove and repeat on the opposite side. Allow time for the local anaesthetic to take effect, checking with the women before proceeding to suture.

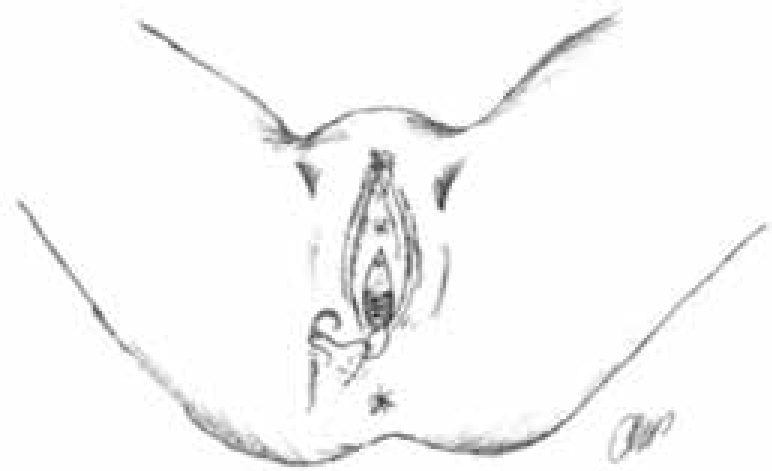

Starting at the apex, undertake a systematic examination after delivery of the perineum, vagina and rectum, assessing the extent of any trauma (Table 2). This should be carried out sensitively and gently. If utilising lithotomy for optimal visualisation, ensure the position is maintained only as long as necessary for assessment and repair (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2014). It is important to gain a second opinion if you are unsure of the degree or extent of trauma incurred, as misdiagnosis of third-degree trauma can have devastating sequelae for the woman (Table 2).

|

|

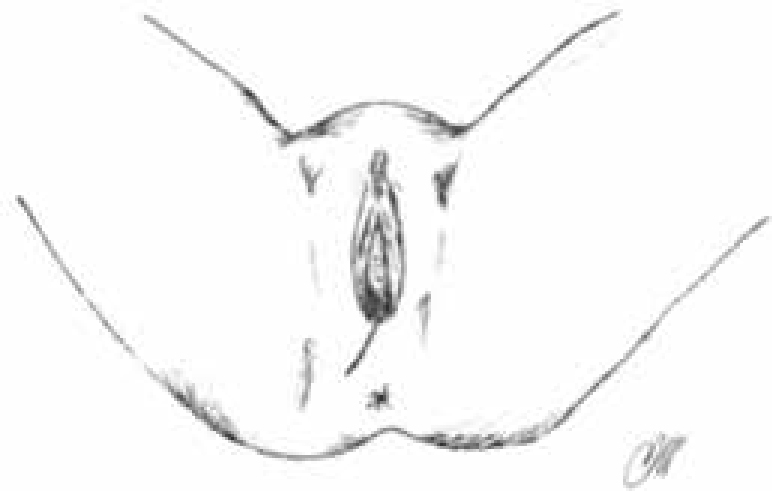

When practising an aseptic technique, current evidence advocates a continuous non-locking method and the use of Vicryl Rapid (gauge 2/0) (NICE, 2014), as it has been associated with less pain (RCOG, 2004) (Figure 1). It is also advocated that all second-degree trauma is sutured and not left to heal naturally. In suturing the vaginal wall, it is vital to identify the apex, inserting the first suture 5–10 mm above and then securing it with a surgeon's square knot. Sutures should be 5–10 mm from the edge of the wound, to ensure that any dead space is closed. It is important to reduce dead space because it could result in bleeding, risking the formation of a haematoma. Continue to suture the vaginal wall utilising a loose continuous non-locking technique down to the hymen remnants, then insert one suture to close the hymen ring. Next, to repair the perineal muscle layer, insert the suture at the level of the fourchette again, using the same continuous non-locking technique (Figure 2). If the trauma is deep it may be necessary to repair in two layers rather than one, ending at the inferior aspect of the trauma. To address the skin layer, reverse the suturing direction at the inferior aspect of the trauma. The skin layer is closed by creating the same continuous non-locking sutures in the subcutaneous layer, alternating between opposite sides until reaching the level of the hymen ring, while ensuring the sutures are not too tight (Figure 3). To finish, place the needle into the vaginal tissue, behind the hymen remnants, and complete with an Aberdeen knot (Figure 4). Again, all needles and swabs must be accounted for before and after the procedure.

After perineal repair is complete, the midwife must inspect the repair to ensure haemostasis has been achieved, which must include a rectal examination to ensure no sutures have entered the rectal mucosa. The woman must be provided with information about the repair, self-care and hygiene of the perineum (Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE), 2011). She should also be instructed on pelvic floor exercises, given expectations for healing and told how to access support if any further problems are incurred (Bick et al, 2010).

|

|

The maintenance of hygiene is very important. Women should be advised to change their sanitary pad regularly. The passing of urine in the first few days may cause some discomfort. Advising women to pour warm water over the perineum whilst voiding will dilute the urine and reduce the discomfort, in addition to keeping the area clean. The area should be gently patted dry from front to back. Dietary advice and adequate fluid intake should also be given to avoid constipation and unnecessary strain on the area.

Conclusion

Midwives are expected to be proficient in the assessment and management of all types of perineal trauma, and to be the lead practitioner for the suturing of first- and second-degree perineal trauma, facilitating continuity of care. Perineal tears can be associated with considerable maternal morbidity as physical complications such as urinary incontinence, dyspareunia and poor perineal alignment. This often results in women having poor self-esteem and lowered psychological wellbeing due to such morbidities having a direct impact upon their life and relationships. As stated, the technique and suture material used for perineal repair can have an impact on the woman's experience, morbidity, and therefore quality of life. It is vital that women receive the correct information regarding the care and expected healing of their perineum and, importantly, where to access help and support if recovery is not as expected.